“Human beings are not born once and for all on the day their mothers give birth to them, but that life obliges them over and over again to give birth to themselves.” Gabriel García Márquez[1]

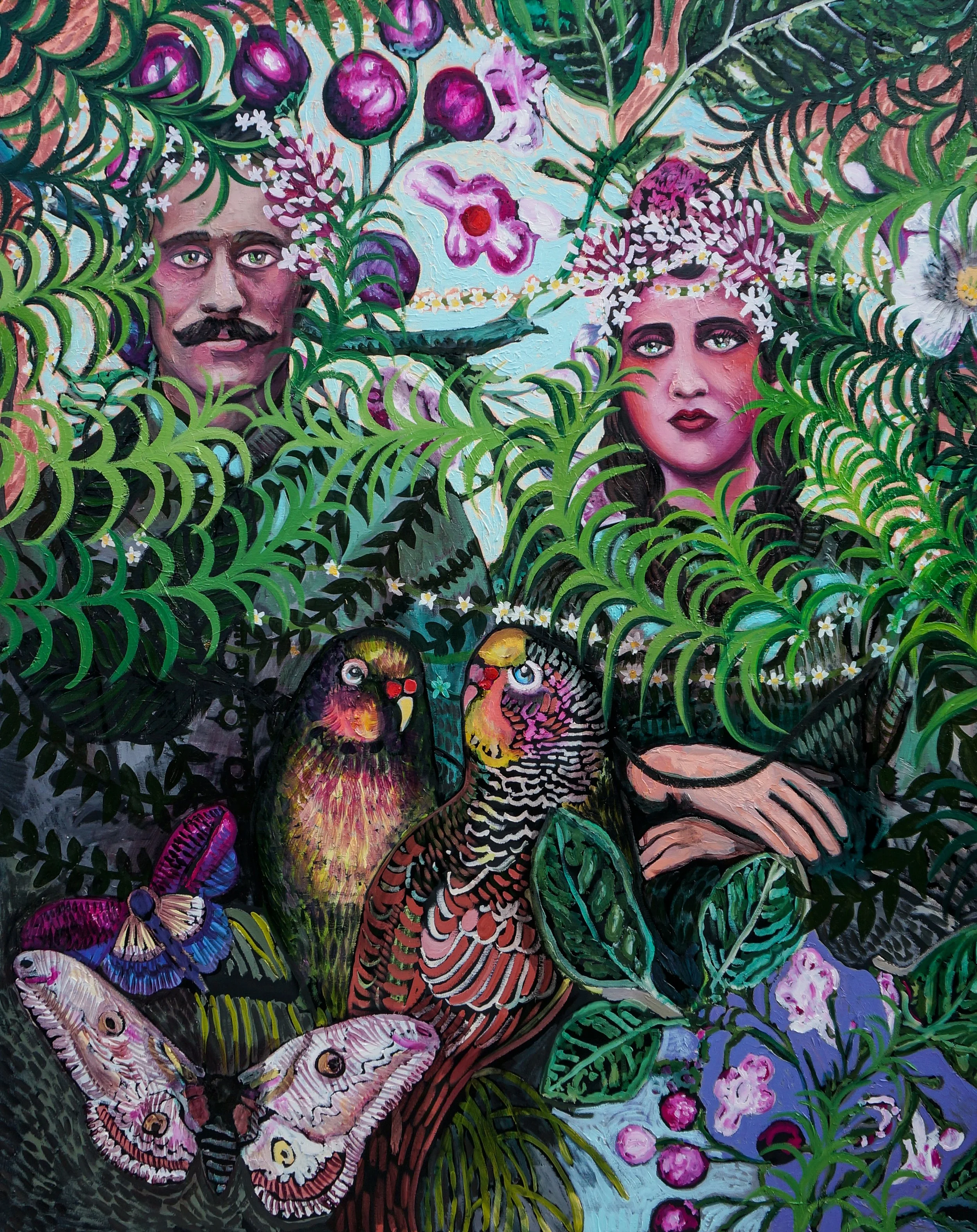

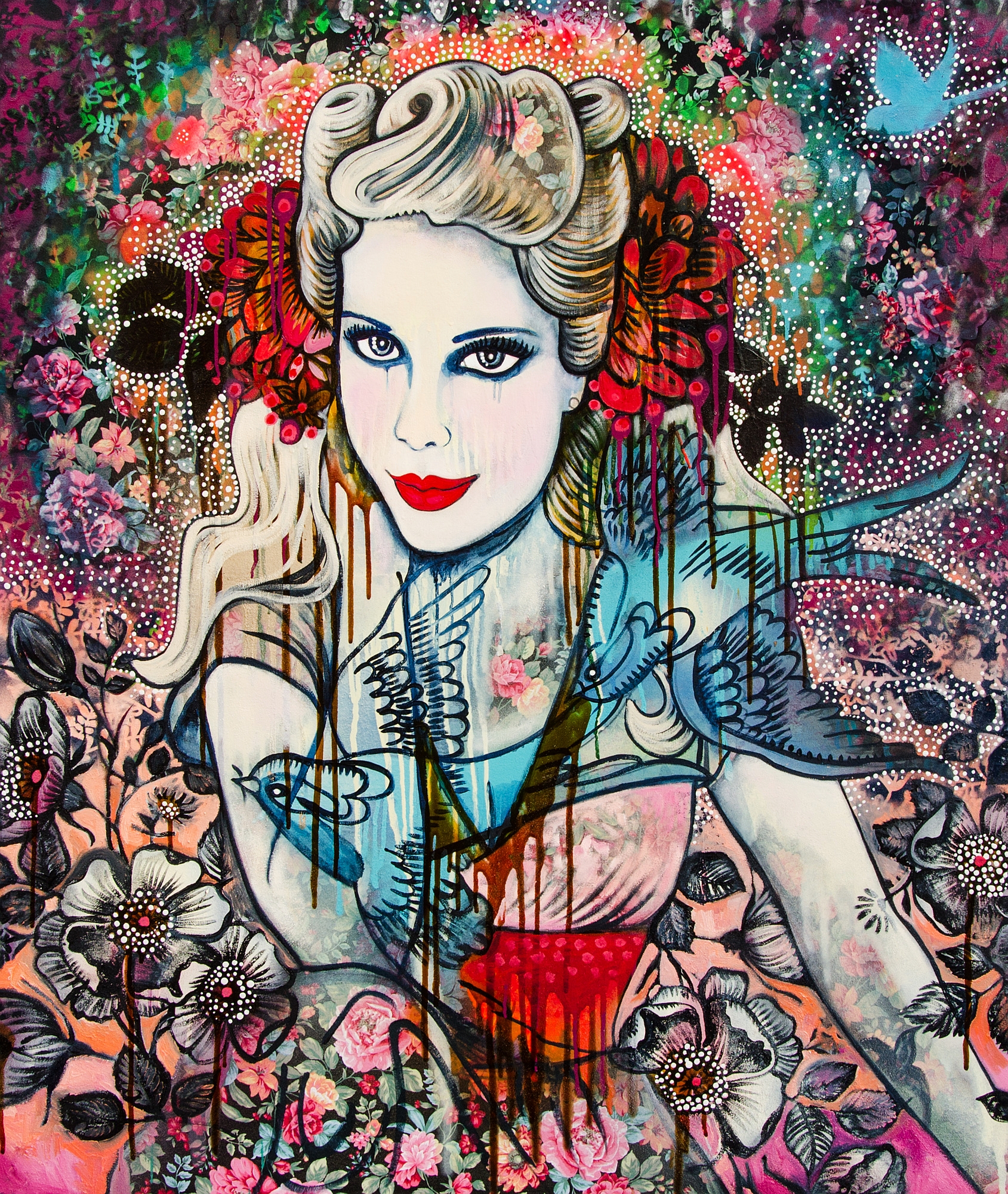

Sarah Hickey’s latest collection, ‘Vessel’, builds upon an oeuvre of images concerned with the conception, birthing and rebirthing of forms, of selves.

Building on and refining Hickey’s trademark stylistic features of stencilled patterning, rich embellishment, floral motifs, birds, and beautiful women gazing skyward or directly at the observer, this collection also introduces the traditional 'still life' into her work. Full, pregnant vases of flowers, dripping and abundant with heavy blooms, spill onto the canvas extending beyond the frames. Thickly applied oils, stylised line and vibrant colour speak of an interior world, of impression and emotion, rather than real, material still life arrangements.

Vessels or vases are classic symbols of the feminine. “Vessels accept, contain, protect and preserve the birth/death/rebirth cycle of life at both the physical and metaphysical level”[2]. The functions of the vessel are holding, immersion or pouring and flowing, all characteristics of the Mother Goddess. In religious symbolism the vessel can be a medium through which something creative and powerful flows, as in a vessel for the Holy Spirit. In alchemical or hermetic lore the vase is the place where miracles occur, the mother's womb, where birth takes shape, and hence the key to the secrets of transmutation[3]. This spiritual notion of the vessel, that the flesh and bone of our physical form contains something as intangible and invisible and hard to define as the soul, prevails throughout Hickey’s work.

Hickey’s vessels and vases are organic, or rather, are bodily organs serving as decorative table pieces. In Ventricle we see a pink fleshy vase, as heart, and more, the flowers folds of skin and pink labia. In Doubleheader (with blooms) and Vessel (with lips), the vases contain the heads of previous femme forms, like stacked babushka dolls, staring outward from their containment. In Mimesis (where bluebirds fly) a beautiful dark haired woman, adorned with bulbous red waratahs and happy bluebirds, holds her hopeful gaze upon a distant horizon. Partially masked by one of the birds, a swollen, vulva-shaped flower, like the root of an orchid, reaches toward the solar plexus like a flaccid phallus. These shapes are reminiscent of the Hindu concept of linga-yoni, an iconic representation of the divine phallus and vagina in union, a union representing the eternal process of creation and regeneration.

As the artist describes, “the women I produce – I see them as avatars, fantasy selves, family – they’re part of my brood.”[4] They are, like all artistic creations, as children birthed, the artist’s heart walking outside her body[5]. And once birthed, no longer constrained only to the artist’s imagination, but free finally to exist in their own right, and to reinvent themselves, again and again, upon each new viewing and in every change of light.

[1] Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in the time of Cholera (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1988)

[2] Jean Raffa, https://jeanraffa.wordpress.com/2014/02/12/the-feminine-symbolism-of-vessels/

[3] Michelle Jennings, http://www.whitewavedreams.com/vasemeaning.html

[4] Louise O’Neil, “A Joining of Souls”, http://sarahhickey.com.au/new-page/

[5] Elizabeth Stone, A Boy I Once Knew: What a teacher learned from her student (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2002)

![Hickey, S. 2016. Girl with Dessert Sombrero and trinity of birds, ink and paint on paper on A3 paper [447100].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/510a425be4b0086d33c40ef2/1463906112837-E4KYHUQCNTDQU60AJ9QO/Hickey%2C+S.+2016.+Girl+with+Dessert+Sombrero+and+trinity+of+birds%2C+ink+and+paint+on+paper+on+A3+paper+%5B447100%5D.jpg)

![Hickey, S. 2016. Heavy thoughts nest like birds on my head, ink and paint on paper on A3 paper [447101].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/510a425be4b0086d33c40ef2/1463906712576-PY5W8JQE71EYJPJI1O3L/Hickey%2C+S.+2016.+Heavy+thoughts+nest+like+birds+on+my+head%2C+ink+and+paint+on+paper+on+A3+paper+%5B447101%5D.jpg)